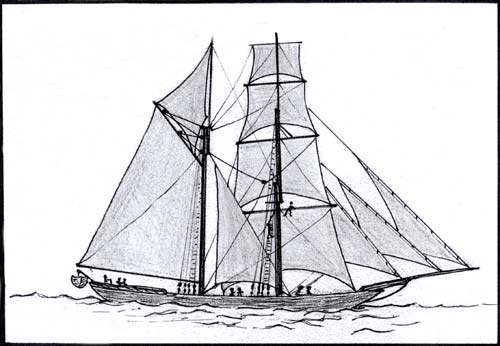

An artist’s impression of the Clara, a 132-ton vessel built in Prince Edward Island, Canada for fishing and sealing. It was purchased in 1864 by two enterprising pioneer families, the Footes and the Peaces, to carry them from Newfoundland to New Zealand. She was an exceptionally fast ship, able to make 11 knots before the wind. Her design was modern, with low, sleek lines, but she was inclined to ship water over the side in rough weather. When the Footes and Peaces reached New Zealand she was put up for auction in Auckland, and sent to Australia. She was wrecked on a reef near Newcastle, New South Wales, on 25 July 1874.

What\'s you story?

Contributed by Elizabeth and William Foote’s great-granddaughter, Alison McMorran of Hamilton

My great-great-great-grandfather, John Foote, left Dorset in the early 19th century and settled in St Johns, Newfoundland, where he set himself up as a merchant trader. He married Jane Dalton, and they had nine children. Their first son and third child, William, my great-grandfather, was born on 26 December 1821.

By 1849 much of the timber near St Johns had been milled and the family, by then with six children, moved to Exploits Island at the mouth of the Exploits River. John Foote and another Exploits resident, William Menchenton, jointly owned a 55-ton schooner, which they had built themselves. Eldest son William was now 28 years old, and had worked in his father’s timber mill and also skippered a fishing boat during the short summer seasons. In 1850 he married Elizabeth Gibbons, the daughter of another mill owner in St Johns. They made their home in Exploits (in 1845 the census recorded the population as 326, with 52 fishing boats, and four in-shore sealing vessels). Their child Frederick, the first of 14, was born there in 1851. Eight of their children were born in Newfoundland, one during the voyage to New Zealand, and the last five in New Zealand. Great-great-grandfather John died in 1852.

In that same year, Elizabeth’s entire family left Newfoundland for New Zealand, taking their milling equipment with them. However, Elizabeth and William remained in Exploits for a further 12 years before the harsh climate caused a downturn in the fishing industry, and subsequently the timber business. They also decided to go to New Zealand and with co-owner Robert Peace bought a 132-ton brigantine, the Clara, built on Prince Edward Island. Her foremast was square-rigged, and the main mast fore-and-aft rigged with a gaff-topsail. This rig enabled her to sail well against the wind, as well as before it. William loaded her with his steam engine, which acted as ballast, and the rest of his saw-milling machinery.

St Johns to Capetown

On Christmas Eve 1864, the Clara sailed out of St John’s harbour, through the Narrows to the Atlantic Ocean. She was skippered by Captain Roper, and the crew included a Norwegian first mate, Ness, second mate, Ball, and six other crew plus two cooks and two stewards. The rest of the ship’s company included William and Elizabeth Foote, their eight children and a servant, Elizabeth’s nephew William Gibbons, Robert Peace and his wife and six children, Mrs Peace’s sister Isabella Ferguson, and some paying passengers – 37 in all. Poultry, geese, pigs and sheep were also penned aboard to provide fresh meat.

All were seasick for the first few days as they ran south before a freezing northerly storm. Ice formed on the rigging and some of the sailors on the dogwatch suffered mild frostbite. By New Year’s Eve, Clara had reached the Gulf Stream and the cabins became stifling hot. New Year’s Day brought another storm, causing Clara to broach and break a jib sheet and the royal halyard. Two days later, the storms had passed and the whole company was able to enjoy a piece of Christmas cake distributed by Mrs Peace.

During the voyage south to the equator, rainfall replenished the water barrels, enabling washing to be done. Feather quilts were packed away and hatch covers were removed to air the cabins. Four ships were sighted on January 12, but none close enough to speak to. On January 16 the Clara crossed the Equator. King Neptune ‘came aboard’ and amid much hilarity all the children were drenched with water. The following day a baby was safely born to Mrs Davey, one of the passengers. One of her young children had died the day before departure, so this child was doubly welcome. She was named Clara Roper Davey after the ship and her captain.

Twenty-four days into the voyage, the first land was sighted. It was Fernanda de Noronha, a Brazilian prison island. There were three islands in the group, high and rocky with lush vegetation on the tops. The Clara came within three miles of them but continued on her journey. Later that night a light was seen on the lee bow, perhaps about one and a half miles away. It came closer and proved to be a large steamer on collision course with the Clara. Extra lights were swung and her bell was rung, but the steamer did not change course. At the last minute Captain Roper fired off two rockets and the steamer did bring her helm to starboard although not soon enough to prevent her rigging and bowsprit tearing through Clara’s mainsail and gaff topsail. The main boom guy was torn away, as well as the stern boat and its davits. Fortunately the boat remained attached to the Clara by her painter. A piece of the steamer’s martingale from under its bowsprit landed on the Clara’s deck and was kept as a trophy.

The steamer stopped and sent across a boat. She was St Helena bound for Liverpool. A shouting match ensued between Captain Roper and the ship’s boat crew who then returned to St Helena, which disappeared into the night. Mrs Foote fainted and parents dashed about looking for their children. All were accounted for and nobody was injured so the crew retrieved the boat, bent on a spare mainsail and continued on their way, everyone very shaken by the near catastrophe.

On January 25 the small but precipitous island, Trinidad, was sighted. Although uninhabited, it had a huge population of gulls and some of the passengers were keen to go ashore to gather eggs. The supplies of bread and potatoes were going mouldy, the salt beef and pork were deteriorating and the preserved salmon in tins from Newfoundland had all spoiled in less than a month. However, Captain Roper deemed it too dangerous and would not allow it.

By the last day in January the ship was 7,000 miles from St Johns with 2,000 miles to Capetown. Clara had proved her speed by passing most of the ships that they had sighted, however, Brilliant, a Danish schooner of about the same size and sailing in the same direction, came close enough to exchange positions of latitude. She was also bound to Capetown, from Antwerp. A two-penny bet was made as to which ship would arrive first, but there is no record of the winner.

The Cape of Good Hope was notorious for its fickle winds, strong currents and sea fogs. As Clara approached within 600 miles, she became a victim to all of these, adding more than 100 miles in extra tacking against wind and current, or lying becalmed in the fog. The ship’s steward, who had shown signs of derangement earlier in the voyage, became quite crazy. Weary, frustrated and demoralised, the ship’s company organised a concert to boost morale, ending with a rowdy singsong. Finally, on February 20, Clara made anchorage in the bay below Table Mountain. The port captain came aboard to check that all passengers were well. He informed them that, as business was very slow there, many people had departed for New Zealand.

Capetown to Melbourne

Fresh meat and supplies were ordered, and nobody wasted time in getting ashore. Most of the crew and male passengers visited the local alehouses to share tales of the sea and of life in the colony. Mrs Peace, a strict Presbyterian and temperance woman, had them all sign a pledge to abstain from intoxicating drink before they went ashore. They did sign it, but the effect lasted less than a day, and a search party was sent out to retrieve some of the men who did not return, including William Foote.

It was a unique experience for the passengers to meet people from such a variety of races – the various tribes of Southern Africa and the imported Asian labourers – and to discover such a wide range of fruit and vegetables. The main mast, which had been sprung in the collision, was repaired. The captain had not mentioned the seriousness of this, so as not to alarm the passengers. The crazy steward was paid off, and replaced.

On the first day of March their thoughts were of ‘home’ in Newfoundland. It was traditionally the day that the ships set out for the ice to seek seals. Two days later, stores were loaded including ten sheep, several pigs, some poultry and fresh vegetables, but, as Friday was not deemed a lucky day to set sail, Clara waited until Saturday morning before slowly sliding out of the bay on a gentle breeze. For the next 10 days, as the wind rose to storm force, Clara pitched and tossed in huge seas created by an uncomfortable combination of headwinds and cross-seas. In those ten days they made only two days worth of progress. The ship headed south looking for the westerly winds in the Roaring Forties, but not until the 17th day were they able to make an easterly course! Flocks of albatross joined the Clara at this point and remained with them much of the way to Australia. The seas were heavy and the wind strong, allowing Clara to make 10 knots for several days.

St Paul’s Rock, midway between the Cape and Australia, was sighted on March 30, 4500 miles from New Zealand. Warmer clothes and feather beds were once again brought out. The company was miserable. Many were suffering from colds. The fresh food was finished and some had to be thrown overboard, unfit to eat. The young boys caught an albatross, but heeding the Ancient Mariner’s tale, let it go again. Nevertheless, when things got desperate, three were killed and eaten.

On Good Friday, a turkey was killed, but as the Catholics were fasting there was all the more for the Protestants. Mrs Peace felt that there was too much ‘rowdyism’ allowed by the captain. She tried to keep her boys apart from the others, ‘as they [would] not be improved by mixing with the others’. She did not approve of William Foote who was inclined to get ‘on the ale’ and become argumentative. Everything was wet, and the food supplies in a poor state, so Captain Roper decided to put in at Melbourne to re-provision and replace some of the rigging. Before they arrived they were treated to an astonishing display of the aurora Australis. The shimmering gold, blue, purple, orange and green curtains of light in the night sky reminded them of their homeland’s aurora borealis – the Northern Lights.

Melbourne to Manukau

The anchor was dropped in Hobson Bay, south of Melbourne, on April 21. Then followed two months of legal action, repairs and an addition to the family. Clara Peace Christian Foote was born ashore in Melbourne on 19 May 1865. She was William and Elizabeth’s ninth child. Some of the fare-paying passengers had complained to the authorities, and Captain Roper was fined £74 for ‘not having sweet and wholesome provisions’, ‘insufficient privy accommodation’, ‘not having a supply of medical comforts’, ‘not producing a Master’s list’, and ‘not having fitted life buoys’. Then the owners, Foote and Peace, were fined £30 ‘for being two berths short, and for not having the flour correctly stowed’.

All but two of the fare-paying passengers left the ship in Melbourne, so there was much more room for the remainder of the voyage. Clara once again headed for the high seas, through Bass Strait and into the Tasman Sea, in fine weather with a light following breeze. Large numbers of sea birds heralded the land, followed by sudden squalls of heavy rain – just the kind of weather that the Newfoundlanders had heard was typical of New Zealand. As the little ship approached the dangerous bar at the Manukau Heads the tide turned, so Captain Roper decided to wait until the following day to make the entrance.

And so it was that on 30 June 1865, Clara followed a schooner, Huia, into the harbour and cast anchor to wait for the pilot. From their anchorage a forest of giant kauri trees could be seen on the northern shores, and although the young Footes did not realise it at the time, this was to be part of their future in their new country. Three Maori pilots came aboard and took the Clara through the winding channels between the sandbars to Onehunga, where at last the Foote family stepped ashore to begin their new life.

Using this item

Private collection

This item has been provided for private study purposes (such as school projects, family and local history research) and any published reproduction (print or electronic) may infringe copyright law. It is the responsibility of the user of any material to obtain clearance from the copyright holder.

Comments

On Christmas Eve, 1864 James

Peter Merchant (not verified)

19 April 2016

Incredible story! And an

Jared Tobin (not verified)

07 March 2012

Add new comment