Story summary

First English–Māori translations

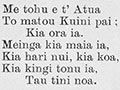

Māori is a Polynesian language, and Tahitian chief Tupaia understood it well enough to translate between Māori and English for British explorer James Cook on his voyage to New Zealand in 1769. Early European settlers needed to communicate with Māori in order to survive, so interpreters on both sides were important. Some missionaries became fluent in Māori, and translated the Bible and other sacred books.

Treaty of Waitangi, publications and Parliament

The Māori translation of the Treaty of Waitangi guaranteed the chiefs ‘tino rangatiratanga’ over their lands, dwelling places and property. Debate over the translation and the meaning of ‘tino rangatiratanga’ has continued into the 2000s.

In the mid-19th century publications were translated from English into Māori, because many Māori could read their own language but did not speak good English. In the late 19th century translators and interpreters were used in courts, government offices and other official settings. Translators often had mixed Māori and Pākehā ethnicity, or were Pākehā who had grown up in Māori communities.

Before 1858 laws were not printed in Māori, even though some important acts affecting Māori had been passed. The first four Māori MPs, elected in 1868, spoke little English, and English-language speeches were often not translated. By the 1880s Parliament employed three translator–interpreters. In 1913 it was ruled that MPs who were fluent in English were not allowed to speak Māori unless an interpreter was there. From the 1930s MPs were permitted to speak Māori if they immediately translated it.

Later 20th and early 21st centuries

Over the 20th century almost all Māori came to speak English, so fewer translators were needed. In 1985 Māori was made an official language, and once again a growing number of institutions began to need translators.

From 1990 MPs no longer had to translate their words if they spoke in Māori. Parliament appointed an interpreter in 1999, and by 2014 there were four full-time interpreters, with simultaneous interpretation in Parliament and on parliamentary television. Māori-language schools were set up and curriculum materials were translated.

There are also interpreters who translate into New Zealand Sign Language.

Works by New Zealand writers have been translated into other languages, including English works translated into Māori. The New Zealand Centre for Literary Translation opened in 2008.