Story summary

Legendary origins of carving

According to legend, carving was discovered by Ruatepupuke when rescued his son, Manuruhi, from the carved underwater village of Tangaroa, the god of the sea.

Carving materials and techniques

The wood used for carving symbolised Tāne, the god of the forest. When carved it was considered to take on the properties of the figures it represented.

Stone or greenstone adzes and chisels were traditionally used in carving. After Europeans brought metal to New Zealand, carvers began to use sharper metal tools.

There were rituals and rules around carving, for example wood chips could not be used as fuel for a cooking fire.

A carver was expected to spend up to 20 years learning about all aspects of carving.

Carving before 1500

The earliest examples of Māori carving are similar in style to carvings from other Polynesian islands. One example is Uenuku, a stylised representation of the rainbow god, which has been compared to Hawaiian carvings.

1500 to 1800

Māori carving developed its own unique style, including the curved patterns and spirals inspired by New Zealand plants such as ferns.

Elaborately carved pātaka (food storehouses) and waka taua (war canoes) showed a tribe’s mana and wealth. When the first Europeans came to New Zealand they were impressed with the skill of Māori carvers.

There was some difference in carving style between regions and different tribes. The main two were the ‘serpentine’ and the ‘Eastern square style’.

19th century

European colonisation had a big impact on Māori culture, including carving. Large carved meeting houses became more common, and expressed the mana of tribes and a Māori world view. One example is Te Hau-ki-Tūranga, carved by Raharuhi Rukupō in the early 1840s.

The Rotorua school

The Ngāti Tarāwhai hapū of Te Arawa had renowned carvers, including Wero Tāroi. He lived in Rotorua, which was a popular tourist destination. The carving style was changed to please European tourists and patrons who bought the work.

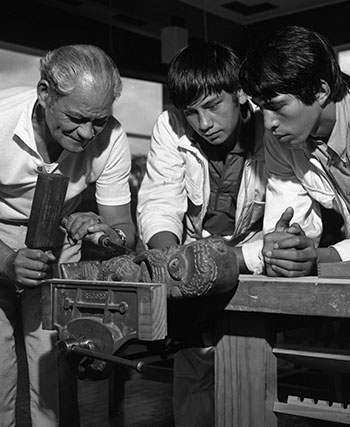

The Rotorua School of Māori Arts and Crafts was founded in 1926. It trained students in traditional carving. Through this programme, many carved meeting houses and dining halls were constructed around the country.

Urban carving

In the second half of the 20th century some carvers still followed the traditional model. However, some (such as Arnold Manaaki Wilson) trained at arts schools.

By the 1970s many Māori lived in cities, and new urban marae were constructed. Cliff Whiting was one carver who worked on new carved meeting houses. His work included the meeting house at Te Papa, and he also restored historic ones.

There was a resurgence of carving canoes, and 23 waka taua featured in a flotilla for the 150th anniversary celebrations of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1990.

Carving in the 2000s

Many urban marae are pan-tribal or multicultural, for example Ngākau Māhaki at Unitec in Auckland, carved by Lyonel Grant.

In 2013 carving is taught at Te Wānanga o Aotearoa, Te Wānanga o Raukawa and Te Puia, the New Zealand Māori Arts and Crafts Institute.