The 19th century was a period of dramatic change as Māori experienced the impact of colonisation. One impact was the introduction of guns, which proved deadly during the intertribal ‘musket wars’. Those who possessed the imported weapons overwhelmed and decimated those who did not. The carved Te Kaha pātaka (storehouse) was dismantled and hidden by its makers, Te Whānau-a-Apanui, when they were threatened by musket-bearing Ngāpuhi. The carving traditions of the north, Hauraki and Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland) seem to come to an abrupt end at this time. The later wars between Māori and the Crown had a further impact. For instance, in 1863 the Crown destroyed more than a thousand canoes on Manukau Harbour just before the invasion of Waikato.

Te Hau-ki-Tūranga

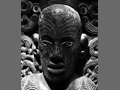

The magnificent meeting house Te Hau-ki-Tūranga, carved by Raharuhi Rukupō, which in the early 2000s was in the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, was completed in the years immediately after the Treaty of Waitangi was signed. It is an example of the transition between a chief’s own house and the much larger communal houses that became the expression of tribal mana in place of waka taua (carved canoes) and pātaka (food storehouses). Te Hau-ki-Tūranga is exceptional not only because it is the oldest existing example of a fully carved meeting house, but because it demonstrates Rukupō’s exemplary skill. He utilised new steel tools to great effect, producing forms that are highly sculptural and inventive in their application of surface patterning. The house was described by Māori leader Apirana Ngata as ‘the finest flowering of Maori art’1 and was upheld by him as the example to be followed by the carving school he established in 1926.

Te Hau-ki-Tūranga is seen as the ultimate expression of mana, of supreme confidence in the Māori world-view, by a tohunga immersed in the customs and lore of his people. Rukupō deeply feared Pākehā encroachment, and by 1867 his world had been shattered, his tribe dispersed and Te Hau-ki-Tūranga confiscated by the government.

Simplified symbolism

In areas most affected by land confiscation and conflict, such as Taranaki and Waikato, the rich carving traditions were obliterated. On the East Coast carving continued under carvers such as Hōne Ngātoto, albeit heavily influenced by western narratives and naturalistic conventions. As Māori became more exposed to Christianity and European cultural influences, their understanding of their own culture’s symbolism started to break down. Carvings began to be read like a picture book – a taiaha (fighting staff) signified a warrior, a naturalistic landscape beneath a chief symbolised his domain.

Multi-use houses

During the period from the 1860s until about 1920, the traditional Māori way of life was disrupted and Māori were regarded by many Europeans as a dying race. As a result of political upheavals, meeting houses were built to fulfil the roles of church, assembly hall and sleeping house, so that communities could gather to respond to the issues at hand. There was little time to carve elaborate houses that indulged the traditions of the past.

Painted houses

There followed an innovative period of painted houses, which made reference to carving in painted form. They are associated with Rukupō’s nephew Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Tūruki, a prophet and war leader, although not all were made under Te Kooti’s influence. These houses drew on western naturalism and narrative figure painting as introduced to Māori in the missionaries’ illustrated books, as well as kōwhaiwhai, tukutuku (woven panels) and whakairo. Such houses were described by traditionalists such as Ngata as a ‘degeneration’ of the art of carving. Yet, as a reflection of the people and time in which they were made, they make a powerful statement. Rongopai at Manutuke and Te Poho-o-Materoa at Awapuni (both near Gisborne) are the best known.