The arrival of English explorer James Cook in New Zealand in 1769 saw the first gifting of taonga (ancestral treasures) by Māori to Europeans. These taonga left an ancient Pacific culture of reciprocity and belonging, and entered a foreign system of legal title and museums. From this time on thousands of taonga were acquired by Europeans. Some were gifted, often as acknowledgements of agreements or relationships. Pākehā also bought, traded for and sometimes stole taonga. Museums and collectors in New Zealand traded taonga with overseas museums and collectors in order to acquire artefacts from overseas. Māori taonga eventually ended up in the collections of almost every major museum in the world.

Modern museums emerged out of the era of Europe’s industrial revolution and imperial expansion. Major powers, including Britain, France, Germany, Spain and the Netherlands, competed to conquer, colonise and exploit world resources. Items collected from indigenous people were hoarded and exhibited in institutions such as the British Museum, providing evidence of colonial expansion.

In the 21st century there are still large collections of taonga in overseas museums. Māori have sometimes tried to repatriate taonga, in particular human remains. In other cases, such as that of the carved house Ruatepupuke in Chicago’s Field Museum, Māori have come to agreements with the museum as to how the taonga should be displayed.

The age of exhibitions

New Zealand’s first museums were established during a time when international exhibitions were immensely popular, following the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. New Zealand sent displays to overseas exhibitions, while a number of exhibitions were held in the colony itself. Generally Pākehā exhibited Māori taonga to illustrate European colonisation and progress. Occasionally, as at the 1876 Philadelphia International Exhibition, Māori were involved in presenting their own interpretations of taonga.

Museums in the colonies

Colonies also set up museums as they established colonial governments, reflecting the European domination of the Americas, Pacific and Asia. In 1852 New Zealand’s first settler government was established in Auckland. In the same year the fledgling nation’s first public museum, the Auckland Institute, opened its doors. This was followed by the Colonial Museum in Wellington (1865), the Otago Museum in Dunedin (1868) and the Canterbury Museum in Christchurch (1870). All placed Māori ‘curiosities’ on public display, mirroring the colonial intent to take over Māori-controlled resources.

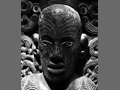

The taking of Te Hau-ki-Tūranga

The carved house Te Hau-ki-Tūranga, from Ōrākaiapu near Gisborne, was built in the 1840s by Raharuhi Rukupō and others of the Rongowhakaata iwi. In 1867 Native Minister James Richmond confiscated the house. It was taken to Wellington and placed in the Colonial Museum, despite protests by Rongowhakaata. The house was still at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in 2011, the year the Crown finally agreed that it would be returned to Rongowhakaata by 2017.

Curiosities, curios and artefacts

The labels museums used to describe taonga changed through time. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries the earliest collections of taonga entered the British Museum as ‘artificial curiosities of the South Pacific’. From the mid-19th century, as traditional Māori society began breaking down under the pressure of land alienation, Pākehā collectors easily acquired taonga and ancestral human remains. Māori items were displayed to local and overseas audiences as ‘primitive curios’ of a declining noble race, which was seen as inevitably giving way to British colonial progress.

By the 1920s anthropology was the dominant discipline for the scientific study of the human race. Taonga became specimens that were collated, exhibited and compared, as examples of ethnography, ethnology or natural history. Archaeology offered yet another new label to explain taonga: ‘primitive artefacts’.

Taonga as ‘art’

In the 1960s the modern art world, led by United States galleries, used taonga as examples of ‘primitive art’. Museums responded in the 1980s, labelling taonga as Māori art. What remained constant, throughout the many changes of how taonga were described by museums, was the way in which they were exhibited. Each era of labels for taonga gave a more accurate description of the belief systems of colonial nations than it did of the originating values of the Māori communities that created them. At the heart of these originating values, ignored by museums, were the obligations of reciprocity that went with the gifting of taonga.