In the mid-1960s and especially in the 1970s new ideas about identity began to have a profound impact on New Zealand. They took root especially among younger people and those at universities or with a university education. As with other significant ideas, the original inspiration came from overseas, and the theories were developed further within New Zealand and expressed in social and political action rather than in major intellectual contributions.

Independent foreign policy

New world views were first prominently expressed in relation to foreign policy, especially in response to New Zealand’s token involvement in the Vietnam War. Following overseas (especially American) examples, there were teach-ins (educational discussions), which spread ideas questioning Cold War assumptions. New Zealanders gave this a strong nationalist slant by arguing for an independent foreign policy. In the long term this bore fruit in the break from the ANZUS alliance with Australia and the United States in 1985.

Māori rights

Some urban Māori, inspired by civil rights and black power ideas from the United States, and decolonisation movements in Africa and Asia, began questioning old assumptions about the place of Māori in New Zealand. Academics like Ranginui Walker applied these ideas to New Zealand, while younger activists campaigned for such issues as promotion of the Māori language, the protection of Māori land and the need to take seriously the promises of the Treaty of Waitangi.

Brown dreams

Donna Awatere emphasised the ‘cultural hegemony’ of white ideas. To free themselves of these, she argued Māori had to think differently – to dream. Her book Maori sovereignty concludes: ‘It is the right of all peoples to dream dreams for themselves, believe in them and make them a reality. This is the right we reclaim in reinforcing the separate reality of our tipuna [ancestors] and making it our own. To do this is to take the first step toward Maori sovereignty.’1

There were some important intellectual contributions such as Donna Awatere’s Maori sovereignty (1984). Awatere drew on international theorists such as Frantz Fanon and Antonio Gramsci to emphasise the power of cultural imperialism.

These ideas found expression in such developments as the creation of the Waitangi Tribunal to review infringements of the Treaty of Waitangi, as well as the establishment of kōhanga reo (Māori-language preschools) and Māori radio and television. There was considerable international interest in such institutions.

Feminism

From 1970 feminist ideas spread quickly. Again initial inspiration came from overseas writers – particularly Betty Friedan in the USA and Germaine Greer, an Australian academic resident in Britain. Early New Zealand feminists put energy into study groups and circulating books. Significant overseas thinkers such as Greer, and the American health activist Lorraine Rothman, visited and spoke to large audiences. By the early 1980s there were feminist bookshops in the main centres. From such intellectual ferment came an impressive periodical, Broadsheet; local books such as Sue Kedgley and Sharyn Cederman’s Sexist society (1972); and penetrating critiques of women’s health by Phillida Bunkle and Sandra Coney. The new ideas inspired political and social change – equal pay, reproductive rights, childcare provision and women’s growing visibility in public life.

Sexuality

Gay men and lesbians also took their lead from overseas ideas of gay liberation. Gay rights activism led to greater tolerance, homosexual law reform in 1986 and the introduction of marriage for same-sex couples in 2013.

Environmentalism

Even in the 19th century some people expressed conservationist ideas, initially encouraged by American publications such as George Perkins Marsh’s Man and nature. In the early 20th century people like the botanist Leonard Cockayne, the author and farmer Herbert Guthrie-Smith and the activist Pérrine Moncrieff articulated strong conservationist sentiments.

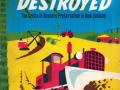

In the 1960s the ideas became more widespread, with a focus on the whole environment, not just the protection of indigenous species. Academics and scientists like John Morton, John Salmon, Charles Fleming, Ian Prior, Alan Mark and Lance Richdale were influential. Salmon’s Heritage destroyed (1960) and Morton’s To save a forest (1984) became classics, while the younger ecologist Geoff Park wrote eloquently of particular places in Ngā uruora (1995). These writers were openly indebted to overseas thinkers such as the Americans Henry Thoreau and Aldo Leopold, and to visitors such as the Briton Graham Searle, whose 1975 book on beech logging had a major impact.

The new ecological thinking had a profound effect – in new legislation such as the Resource Management Act 1991, and in pioneering work to save endangered species, especially birds. Such measures attracted some international attention.

Anti-nuclear ideas

The nationalist drive for an independent foreign policy and the new environmentalism combined in a strong anti-nuclear movement. There were few intellectual reflections of this, but there were powerful political acts such as the frigate sent to oppose French nuclear testing in the Pacific in 1973 and the 1984 refusal to admit nuclear-powered or -armed US ships, which culminated in the passage of anti-nuclear legislation. As so often in the past, ideas that had emerged internationally took on unusual strength in New Zealand and through their implementation attracted interest from the wider human community.