Māori

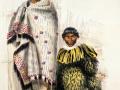

Māori always regarded the kiwi as a special bird. They knew it as ‘te manu huna a Tāne’, the hidden bird of Tāne, god of the forest. Kiwi feather cloaks (kahu kiwi), originally made by sewing kiwi skins together, were taonga (treasures) usually reserved for chiefs. Kiwi feathers, now woven into flax cloaks, are still valued. Māori also ate kiwi, preserving them in the birds’ fat, and steaming them in a hāngī (earth oven).

A taste of kiwi

One of the few Europeans to eat kiwi was the late-19th-century West Coast explorer Charlie Douglas. He wrote that kiwi eggs made great fritters when fried in oil from the kākāpō, but was less complimentary about the meat. After spraining an ankle he came across two kiwi, and being famished, he ate them. He described the taste as ‘a piece of pork boiled in an old coffin’. 2

Early Europeans

From the first, Europeans regarded kiwi as unusual birds. The first skin was taken to England in 1812 and inspired the first illustration of the bird, in which it looked more like a penguin. As early as 1835, the missionary William Yate described the kiwi as ‘the most remarkable and curious bird in New Zealand.’ 1 In 1851, the first living bird was sent to England as a specimen for the London zoo.

Use as an emblem

As the kiwi began to disappear from the bush, its image began to appear as an emblem. In the second half of the 19th century, the kiwi was used as a trademark – for veterinary medicines, seeds, drugs, varnishes, insurance, on the Auckland University College crest, and on Bank of New Zealand notes.

When the first New Zealand pictorial stamps were issued in 1898, the kiwi was on the sixpenny stamp. About 1899, one observer said, ‘From the fact that bank notes, postage stamps and advertisement chromos generally have a portrait of this unholy looking bird on them, it is evident that the kiwi is the accepted national bird of New Zealand.’ 3

National symbol

In the 20th century the kiwi began to represent the nation. In August 1904 the New Zealand Free Lance printed a cartoon which showed a plucky kiwi growing into a moa after New Zealand’s 9–3 rugby victory over Great Britain. This was possibly the first use of the kiwi in a cartoon as a symbol for the nation. The next year the Westminster Gazette printed a cartoon of a kiwi and a kangaroo going off to a colonial conference. In 1905 Trevor Lloyd also drew his first sporting cartoon using a kiwi when he showed the bird unable to swallow Wales following the defeat of the All Blacks rugby team. Lloyd more often used a moa as a symbol for the All Backs during that tour, but by 1908 the kiwi had become the dominant bird symbol in cartoons, especially sporting ones.

Besides the moa, other symbols for New Zealand at this time included fern leaves, a small boy and a young lion cub.

‘Kiwis’

Until the First World War, the kiwi represented the country but not the people – they were En Zed(der)s, Maorilanders or Fernleaves. During the First World War, New Zealand soldiers were often described as Diggers or Pig Islanders. But by 1917 they were also being called Kiwis. It was probably not because they were thought to be, like the birds, short, stocky scrappers – this was a more common image of Australians, while New Zealanders liked to emphasise their stature and good manners. It was simply that the kiwi was distinct and unique to the country.

The kiwi had appeared on military badges since the South Canterbury Battalion first used it in 1900, and it was taken up by several regiments in the First World War. Cartoonists also used the bird often during the war to symbolise New Zealand. At the end of the war New Zealand soldiers carved a giant kiwi on the chalk hills above Sling Camp on Salisbury Plain in southern England.

An Australian boot polish called Kiwi was widely used in the imperial forces. It was named by the company’s founder, William Ramsay, in honour of his wife’s birthplace.