New Zealand International Exhibition, Christchurch, 1906–7

The government and tourist initiatives that shaped New Zealand’s international displays were in evidence at the Christchurch exhibition of 1906–7. Premier Richard Seddon was the prime mover, and the government paid for the exhibition held on 5.7 hectares in Hagley Park. Seddon saw the fair as demonstrating that New Zealand was a great country.

Big building

The Christchurch exhibition was displayed in a huge, 400-metre-long building in French Renaissance style. It was described as ‘a palace of white and gold above the oak trees’.1 The domed entrance, flanked by two towers, was decorated with the greeting ‘Haere mai’ (welcome). The building had a chequered history – the foundation stone was laid on 18 December 1905, but a sudden whirlwind on 20 January 1906 demolished large parts, and the experience was repeated in another gale the following month. Eventually 975 kilometres of timber were used in the largest structure ever built in New Zealand.

To encourage tourism, there was a large fernery, a geyserland in miniature, walls displaying stuffed game and photographs and paintings of beautiful New Zealand. A Māori pā, featuring Māori wearing traditional clothing, was located beside ‘Wonderland’ amusement park, with a water chute, helter-skelter and sideshows.

The government was represented by displays from no fewer than 13 departments. The Department of Labour court showed off New Zealand’s role as the ‘social laboratory of the world’, by contrasting New Zealand-made goods with those produced in British sweatshops.

The exhibition also showed off the country’s material progress, with arches of wheat, piles of corn and bags of kauri gum. There was an art gallery, a major British art display and a concert chamber that hosted both a professional orchestra directed by Alfred Hill and the Besses o’ th’ Barn band from Manchester. There were contributions from Britain, Canada, Fiji and Australia.

Almost 2 million people visited the fair (twice the national population at that time) during its six months.

Itinerant meeting house

The Mataatua meeting house, which had previously been put on display at the 1879 Sydney Exhibition, the 1880 Melbourne Exhibition and the 1924–5 Wembley Exhibition, travelled back to Dunedin’s New Zealand and South Seas Exhibition. It would remain in Dunedin, in the museum, until eventually given back to Ngāti Awa in 1996. It was restored and reopened on its original Whakatāne location in 2011.

New Zealand and South Seas International Exhibition, Dunedin, 1925–26

Following the Christchurch fair there were smaller industrial shows – a Coronation Exhibition in Wellington in 1911; an Industrial, Agricultural and Mining Exhibition in Auckland in 1913–14; a British and Intercolonial Exhibition in Hokitika in 1923–24; and an annual Dominion Industrial Exhibition held in Christchurch in 1922, Auckland in 1923 and Wellington in 1925.

Dunedin’s New Zealand and South Seas International Exhibition, which began in 1925, was on a different scale. Promoted by the Otago Expansion League in response to the population and economic drift north, it was funded by a company that offered 100,000 £1 shares, and a £50,000 government subsidy. The location was reclaimed from Lake Logan, and Edmund Anscombe, the architect, designed seven pavilions linked by covered walkways around a grand court of reflecting pools leading to the domed Festival Hall. There was an art gallery, a fernery (with a waterfall and streams) and an amusement area with seven major rides, notably the scenic railroad and the fun factory with a large comic-face entrance.

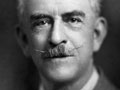

Exhibition man

Edmund Anscombe, who was the architect for both the 1925–26 and 1939–40 exhibitions, was a fanatical exhibition man. At the age of 14 he went to Melbourne to see the 1888 exhibition, he probably visited the 1889 New Zealand and South Seas Exhibition in Dunedin, he worked as a builder at the 1904 St Louis Exposition and, in addition to designing the 1925 exhibition, he claimed to be its instigator.

The themes of the exhibition were:

- the manifestation of the British Empire’s size and strength, reflected in displays by British government and industry, Australia, Canada and Fiji

- the progress achieved by New Zealand’s European pioneers

- New Zealand-made goods displayed in the 1.2-hectare New Zealand manufactures pavilion

- the role of the New Zealand government, which showed off the work of 15 departments.

There was an education court, a women’s court and a motor pavilion. More than 3 million people visited the show, making it the most popular in New Zealand history.

New Zealand Centennial Exhibition, Wellington, 1939–40

Set on a 22.5-hectare site in Rongotai, the centennial fair was designed to mark New Zealand’s centennial by illustrating the progress of the country, rather than to sell goods. A huge frieze at the base of the 46-metre-high tower illustrated this, as did large statues of a pioneer man and woman. The art deco lines of Edmund Anscombe’s design of the exhibition buildings, richly illuminated in colour by electricity, suggested an exciting future.

The fair was organised by a limited liability company; but the government gave a £50,000 grant and several loans. The government court, with 26 departments, evoked a progressive benevolent welfare state complete with a talking robot, Dr Well-and-Strong.

Exhibition numbers

The Centennial Exhibition buildings required 7,080 cubic metres of timber, 60,387 square metres of asbestos, 350 tons of nails, 200,000 bolts, 5,574 square metres of glass, 68,191 litres of paint, 37,000 lights and 3,594 kilometres of wiring. In all, 2,641,043 people visited.

There was a dominion court, with a massive diorama of the country, and women’s and Māori courts. Britain and Australia had their own buildings.

Playland, the amusement park, was popular, with the Cyclone roller coaster, the Crazy House and the Laughing Sailor particular highlights. The outbreak of war affected attendance, which, at just over 2.6 million, was lower than the 1925–26 Dunedin exhibition.

Later exhibitions

The Centennial Exhibition inspired Otago (in 1948), Canterbury (in 1950), Southland (in 1956) and Marlborough (in 1959) to put on provincial centenary industrial fairs. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, as the country encouraged domestic production, Christchurch and Wellington, with their industries fairs, had annual displays of manufactured goods.

In 1990 Sesqui, the celebration of New Zealand’s sesquicentennial (150th anniversary) was a strikingly unsuccessful attempt to hold a modern celebratory exhibition and amusement fair. It closed after a few weeks. The era of the New Zealand fair was over.