Page 1: Biography

Muldoon, Robert David

1921–1992

Accountant, politician, prime minister

This biography, written by Barry Gustafson, was first published in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography in 2010.

Early life and schooling

Robert David Muldoon (known as Rob or Bob) was the only son of James Henry Muldoon, a government inspector, and his wife, Amie Rusha Browne. He was born in Auckland on 25 September 1921. His paternal grandfather, James Henry Muldoon (senior), was a Methodist evangelist and social worker in one of Auckland’s poorest working-class areas. His maternal grandmother, Jerusha (Rusha) Browne, brought up three children alone after being deserted by her husband. Her admiration for the Liberal and then Labour parties was very evident to her grandson, who spent many hours in her company during his youth.

When Rob Muldoon was seven his father, a staff sergeant who served in Egypt and Europe for over three years during the First World War, entered the Point Chevalier psychiatric hospital. He remained there until his death in 1946. Rob was told that his father became partially paralysed and lost his memory and the power of speech because of post-war psychosis and the stress of business failure – but he was also suffering from syphilis.

Rob’s mother worked long hours making furniture covers to support herself and her son and pay off the mortgage on a small house at Western Springs. When Rob was five, a pointed dowel on the front gate pierced his cheek, breaking the muscle and leaving him with a distinctive scar and lopsided smile.

Rob went to Mt Albert Primary and Kōwhai Intermediate Schools before winning a Rawlings scholarship to Mt Albert Grammar School, which he attended from 1933 to 1936. Apart from usually being near the top of the class in English, he did not have a particularly distinguished academic record, despite achieving an exceptionally high non-verbal intelligence test score in the fifth form.

Rob matriculated in his fourth year but lack of funds removed any possibility of his going to university. He worked first as an office boy at Fletcher Construction, and then took a similar post at the Auckland Electric Power Board. In his spare time he was active in the Mt Albert Baptist Bible class and the YMCA, and studied accountancy through Hemingway’s correspondence courses.

Professional and political education

In November 1940, shortly after his 19th birthday, Robert Muldoon enlisted in the army. In 1942, after reverting from sergeant to private at his own request, he was posted to New Caledonia, where he was again promoted, to corporal. In late 1944 he sailed for Egypt and Italy, where he joined D Company of the Divisional Cavalry Battalion in March 1945 and took part in fighting at the Senio and Gaiana River crossings, and in the capture of Trieste.

Muldoon was admitted to the New Zealand Society of Accountants as an associate registered accountant in November 1942 and completed his accountancy exams in Italy in May 1945. When the war ended he took up an armed services educational bursary to study modern management accounting in England, arriving just before Christmas 1945. He worked for Robson, Morrow and Company in London, auditing companies throughout Britain. After 12 months he passed the final exams in cost accounting and became the first overseas student to be awarded the Leverhulme Prize for the highest marks.

After returning to New Zealand in 1947, Muldoon joined an Auckland accountancy firm, which became Kendon, Mills, Muldoon and Browne when his cousin Graham Browne became a partner.

In 1956 Muldoon became a Fellow of the New Zealand Society of Accountants and was also elected president of the New Zealand Institute of Cost Accountants. In this position he was involved in the integration of the Institute into the Society. That same year he organised the first joint cost and management seminar. In 1957 this role earned him the society’s Maxwell Award, given for furthering the community’s knowledge of cost and management accounting.

In 1947 Muldoon joined a new junior branch of the National Party in Mt Albert and in March 1948 became its chairman. In October that year he was elected chairman of the Auckland Divisional Junior Nationals. He was re-elected in 1949, the year that the National Party under Sidney Holland became the government for the first time. The Junior Nationals debated among themselves and against other teams in the Auckland Debating Society, and Muldoon was a very enthusiastic participant.

The Junior Nationals also enjoyed dances and picnics, and many members became romantically involved with one another. In early 1948 Muldoon started going out with Thea Dale Flyger, a Junior National from the North Shore who had studied accounting and worked in the costing office of Holeproof Ltd. They were married at Holy Trinity Church, Devonport, on 17 March 1951. Thea’s father, a builder, helped them build a house in Lake Road, Devonport, and later a bach (holiday house) at Hatfields Beach. They were to have two daughters and a son.

Throughout the 1950s Muldoon was an avid gardener, joining the Takapuna Horticultural Society in 1951. He became president of both the Auckland Lily Society and the Auckland Horticultural Council and was made a Fellow of the Royal Institute of Horticulture in recognition of his expertise and contributions.

National MP

Rob Muldoon tried repeatedly throughout the 1950s to become a member of Parliament. In 1951 he unsuccessfully sought National’s candidacy for Mt Albert. In 1954, after unsuccessfully seeking nomination for Waitematā, he stood in Mt Albert but lost to the Labour candidate. In 1957 he was selected for Waitematā but again lost to Labour. Finally, in 1960 he won selection – and the election – in the marginal seat of Tāmaki, which he was to hold for the next 31 years.

Muldoon was widely regarded as a very good constituency MP, always accessible and willing to assist constituents. Social and boundary changes in the electorate helped change it into a National Party stronghold. Muldoon’s strong electorate organisation numbered some 4,000 members at its peak. It was very active and influential in the wider National Party, becoming known as ‘the Tāmaki mafia’, a term disliked by Muldoon, who was seen as ‘the godfather’.

In the House, Muldoon became friends with other new National MPs, notably Duncan MacIntyre and John Bowie (Peter) Gordon. The three became known as ‘the Young Turks’ because of their criticism of senior National ministers. Muldoon in particular proved to be a well-prepared debater, willing to speak on a range of topics with authority and humour. He developed a deserved reputation as a counterpuncher who saw attack as the best means of defence, and who believed that he should always retaliate if anyone attacked him.

Muldoon was fortunate in 1961 to be appointed to the Public Accounts Committee, which in 1962 became the Public Expenditure Committee, with enhanced powers to investigate and report on the efficiency of government departments and to act as a watchdog on the use of public funds. Its members became well-informed on all aspects of government and able to participate in a wide range of debates in the House.

After the 1963 election, Prime Minister Keith Holyoake appointed Muldoon as under-secretary to the minister of finance, Harry Lake, who made Muldoon responsible for overseeing the introduction of decimal currency. Muldoon annoyed the public by dismissing widespread criticism of the proposed new coins. Holyoake rebuked him and a nationwide poll allowed the public to choose new coin designs from those originally submitted.

Cabinet minister

As under-secretary, Muldoon attended meetings of the Cabinet Committee on Economic and Financial Policy, which gave him access to information he eagerly devoured. He also became chairman of the Public Expenditure Committee and, as Finance Minister Harry Lake’s proxy, sat on the Cabinet Works Committee. Senior ministers and bureaucrats came to fear his examination, and his aggressive manner antagonised them. As a result, when Prime Minister Keith Holyoake consulted cabinet colleagues on additions to his ministry after the 1966 election the consensus was to appoint Duncan MacIntyre, Peter Gordon and David Thomson but not Muldoon.

Three months later, on 10 February 1967, Holyoake added a chastened Muldoon to cabinet as minister of tourism and associate minister of finance. At the time New Zealand’s wool prices had collapsed, creating a serious economic crisis. Holyoake and Lake were engaged in a major battle within Cabinet against Tom Shand, who wanted a markedly more radical approach to the crisis than the prime minister and minister of finance would accept. Eleven days later, Lake died suddenly. Holyoake refused to appoint Shand and, after Jack Marshall declined the post, the prime minister gave the position to Muldoon. He was to be minister of finance for 14 of the following 17 years.

Henry Lang, the secretary of the Treasury, found Muldoon to be an intelligent, hardworking and pragmatic minister, who also revealed considerable integrity. In time though, Lang came to dislike Muldoon’s personality, lack of imagination and unwillingness to adopt new ideas.

Muldoon believed that problems in the economy should be dealt with as they emerged, not left to an annual budget, so he introduced the practice of ‘mini-budgets’ and continual fine-tuning of the economy. The first mini-budget was on 4 May 1967, when he dampened down demand by increasing a range of indirect taxes and government charges. He also moved to cut and hold government expenditure, explaining his measures to the wider public. In November he reluctantly recommended the devaluation of the currency.

Muldoon was conservative when it came to changing the tax system, and opposed a suggestion in the Ross Committee Report on taxation that there should be a move from direct to indirect taxation. He believed that would increase costs, and the tax burden would fall more heavily on lower-income earners. He also tried to defend the welfare system, and extended it into new areas, including in 1968 a domestic purposes benefit for deserted wives and single women with dependent children. In 1968–69 he was also deputy chairman, to Marshall, of a national development conference to plan indicatively the future of New Zealand’s economy.

Party leader

Many people disliked Robert Muldoon’s abrasive personality and populist appeal. From 1967 opponents referred to him with contempt as ‘Piggy’ Muldoon. But others, who became loosely known as ‘Rob’s Mob’, admired the direct and combative politician, who certainly polarised public opinion but claimed to understand and represent ‘the ordinary bloke’ against the elites. Their loyalty was as much to Muldoon personally as to the National Party.

Although it appeared likely that National would lose the 1969 election, it won its fourth victory in a row. Prime Minister Holyoake told his caucus colleagues that they could thank Muldoon for the victory, and certainly the minister of finance’s barnstorming campaign throughout the country was generally regarded as a major reason for the win. It also raised the possibility that Muldoon rather than Jack Marshall might succeed Holyoake as National’s leader.

When Holyoake stood down, however, in February 1972, Marshall defeated Muldoon, who became the new deputy leader. Marshall lost the 1972 election and on 9 July 1974 was replaced by Muldoon, whose supporters convinced a majority of caucus that Marshall could not defeat Labour’s Norman Kirk. Many in the National Party organisation, however, were upset at Marshall’s removal and never accepted Muldoon as the ideal National leader.

The day after Muldoon became leader, The rise and fall of a Young Turk, the first of four autobiographies he was to write over the following 12 years, was published. Within four months it was reprinted three times and sold over 28,000 copies. The sequels were Muldoon (1977), My way (1981) and Number 38 (1986). He also wrote The New Zealand economy: a personal view (1985).

Muldoon was an extremely effective leader of the opposition in 1974 and 1975. His task was made easier by the death of Kirk in August 1974. The Labour government, now led by Wallace (Bill) Rowling, also had trouble dealing with an economic crisis following the first international oil shock and a downturn in New Zealand’s terms of trade.

Muldoon traversed the country attracting huge and enthusiastic audiences. He denounced Labour’s alleged economic mismanagement and Kirk’s decision to stop a Springbok rugby tour. He also promised to establish a national superannuation scheme, funded out of taxation, which would pay individually to all men and women a pension of 80% of the average ordinary-time weekly wage, less tax but in addition to any other income. It was one of the most costly and attractive election promises in New Zealand’s history.

Labour countered with a ‘Citizens for Rowling’ campaign to draw attention to Rowling’s strengths, but more importantly, by comparison, to alleged defects in Muldoon’s personality and character. Labour television advertising showed a child holding a pig while a background song alluded to a dictator, and few believed Labour claims that there was no intent to refer to ‘Piggy’ Muldoon. Holyoake and many others rallied to Muldoon’s defence and the negative campaign was largely counterproductive. National won the 1975 election by 55 seats to Labour’s 32, an exact reversal of the outcome three years before.

Prime minister

Muldoon’s intelligence, access to information, grasp and recall of detail and capacity to identify issues, along with his forceful personality, ability to persuade and status as prime minister, made him dominant in the governments he led between 1975 and 1984. Holding the post of minister of finance reinforced that dominance but also overloaded him and made him open to criticism. When he chaired cabinet or caucus, other ministers and members found it difficult to appeal against the recommendations of the minister of finance without the prime minister taking it personally.

Some very able ministers, not least Brian Talboys, Duncan MacIntyre and Bill Birch, invariably supported Muldoon, and, once he had a majority in cabinet, he was able to use executive collective responsibility, his powers of persuasion and clever use of the whips to sway a majority in caucus. As a result a minority of ministers and members who disagreed with specific policies, especially in regard to the economy, became increasingly frustrated, resentful and alienated from him.

Muldoon was also assisted after 1975 by the creation of a new and separate Prime Minister’s Department. This provided liaison between the prime minister, the bureaucracy and major pressure groups. It kept Muldoon abreast of developments, provided information and enabled him to react quickly and knowledgeably.

Muldoon’s tenure as prime minister and minister of finance coincided not only with the long-term structural change in New Zealand’s economy but also with the advent of television. Despite his contempt for interviewers he was quite prepared to engage them and, when necessary, speak over or around them directly to viewers. Only Norman Kirk and, later, David Lange could match him. Although many journalists feared and even hated Muldoon, he fascinated them.

Muldoon constantly became embroiled in controversies, many of his own making. Two major ones were his 1976 revelation in Parliament that the prominent Labour MP Colin Moyle had been questioned by the police in regard to possible homosexual soliciting, and Muldoon’s appointment of Keith Holyoake as governor general in 1977. He also used Security Intelligence Service material to publicly identify trade unionists he claimed were communists; attacked his colleague George Gair for promoting the liberalisation of abortion; encouraged visits of US nuclear-capable warships; and, despite being a party to the Commonwealth leaders’ Gleneagles agreement in 1977, refused to stop a Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand that split the country and led to unprecedented civil disorder in 1981.

Muldoon’s attitude to Māori was somewhat ambivalent. He strongly opposed the return of Bastion Point to Ngāti Whātua but developed a strange personal relationship with Māori gangs, especially Black Power, encouraging them to form work trusts and assisting them to find accommodation.

As prime minister, Muldoon frequently visited foreign countries and attended international meetings. He was not always tactful, particularly at Commonwealth prime ministers’ meetings where he resented criticism of New Zealand by leaders whose own countries were not model democracies. As in domestic politics, he was prone to attack the messenger as well as the message and his targets included Commonwealth Secretary General Shridath Ramphal, Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser and US President Jimmy Carter, whom Muldoon dismissed as merely a peanut farmer from Georgia.

Economic policy and problems

Faced with severe and ongoing balance-of-payment problems, high internal inflation, high interest rates, and increasing unemployment and industrial strife, the 1975–84 Muldoon government tried hard to increase the production and export of traditional wool, meat and dairy products, through subsidies and tax incentives. Concurrently there was an attempt to diversify the economy through the creation of new industries such as aluminium, steel, forestry, fishing, horticulture, viticulture and tourism, and to develop energy projects to reduce New Zealand’s dependence on increasingly expensive imported liquid fuels.

These expensive new industries and energy projects, which Muldoon called his ‘growth strategy’, became more commonly known as ‘Think Big’. The government also sought to extend free trade with Australia, signing a Closer Economic Relations (CER) agreement in December 1982. Throughout this time, labour relations became increasingly strained and Muldoon would not allow free-range bargaining. He also resisted the abolition of compulsory trade-unionism.

Although Muldoon and National remained in office by winning a majority of the seats at the 1978 and 1981 elections, the Labour opposition won more votes nationally in both elections. This led to increasing frustration and bitterness among Muldoon’s critics and opponents. Within the government’s own ranks there was growing opposition to Muldoon personally and to his economic policies. In October 1980 he only survived as leader because Brian Talboys refused to contest the position, despite other senior ministers organising a majority of National MPs to oust Muldoon in his favour.

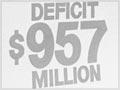

In June 1984 Muldoon was struggling to end a government-imposed freeze on wages, prices and interest rates without causing runaway inflation and an escalation of industrial unrest. He was also facing difficulties finalising his budget and resisting advice and pressure to devalue the currency. The Labour Party was revitalised under its new leader, the charismatic David Lange, who was proving more than a match for a tired Muldoon. The last straw, which led Muldoon to ask the governor general to dissolve Parliament and call an early election, was the decision of MP Marilyn Waring to leave the National caucus and vote in favour of nuclear-free legislation being proposed by Labour.

Defeat and recovery

Robert Muldoon’s 1984 election campaign was perfunctory and far less effective than his earlier ones. With the National Party’s vote split by the new right-wing New Zealand Party, led by the businessman Bob Jones, Labour won a resounding victory. It gained 56 seats to the 37 National retained and the two won by Social Credit. Immediately after the election, held on 14 July, the Reserve Bank and Treasury persuaded the incoming Labour government that devaluation was essential. A reluctant Muldoon, after some confusion, carried out David Lange’s instructions to do so.

It was agreed that Muldoon remain acting as National’s leader until February 1985. Fear that he might try to remain in the leadership position longer led to caucus holding a leadership vote on 29 November 1984. Jim McLay became National’s new leader, defeating four other candidates including Muldoon, who received only five of the 37 votes.

Muldoon kept a low profile for about six months after losing the leadership, but became increasingly annoyed by the growing influence of the New Right on the National Party and a willingness to scapegoat him personally for everything that had gone wrong in the past. Others also started to defend Muldoon and his legacy and during 1985 some 20,000 people joined an organisation called the Sunday Club, whose main aim appeared to be to rehabilitate Muldoon to National’s front bench if not to the leadership. There were even suggestions that Muldoon might split the National Party and become leader of a new conservative party.

Muldoon’s criticism of McLay and Ruth Richardson led to McLay demoting him to the bottom ranking in the caucus. Muldoon and his supporters then backed Jim Bolger in a successful challenge to McLay on 26 March 1986 and Muldoon returned to the front bench as foreign affairs spokesperson.

While prime minister, Muldoon had campaigned persistently overseas about the dangers to the world economy of third-world debt and the need to reform the international monetary system. He continued to do so after 1984, criticising some of the policies of the International Monetary Fund and raising the prospect of another stock-market crash similar to that of 1929. At conferences in Washington DC in 1985 and Zürich in 1986 he came into contact with the Global Economic Action Institute (GEAI), whose goal was international economic stability, especially financial stability.

After participating in a number of GEAI conferences and preparing some reports for them, in 1988 Muldoon succeeded Eugene McCarthy, the onetime US presidential candidate and senator, as GEAI’s chairman. He held the post until 1991, chairing conferences in Africa, the United States, Taiwan, Germany, Japan, China, Hungary and Russia.

Final battles

The Labour government was re-elected at the 1987 election with many former National voters supporting Roger Douglas’s free-market economic policies. Of National’s urban strongholds only Muldoon’s seat of Tāmaki recorded a safe majority. After the election, National Party leader Jim Bolger appointed Ruth Richardson as finance spokesperson and Muldoon again withdrew to the back benches, from which he trenchantly criticised both Labour and Richardson.

National defeated Labour in the 1990 election, and Richardson as minister of finance pursued similar policies to Douglas. Muldoon, acting almost as an independent MP, launched attacks on her inside and outside the House. He objected to the retention of the superannuation surtax, to welfare cuts, and to the influence of the Business Roundtable. By then, however, he was persistently ill, tired and deeply disheartened.

Muldoon had developed diabetes in the early 1980s and also had a bowel-cancer operation in December 1986. Three years later, in December 1989, a bacterial blood infection did not respond to antibiotics, his heart was seriously damaged, and the aortic valve was replaced. He was very ill and took some three months to recover. Despite this, he stood and was re-elected in Tāmaki at the 1990 elections with his largest ever majority: 7,592 votes.

In November 1991 Muldoon angrily told caucus that he thought he would resign, predicting that with its current policies National would be lucky to survive the next election. He confirmed his retirement on Radio Pacific 10 days later. He had served 31 years as an MP when he gave his valedictory speech on 17 December 1991.

On Sunday afternoons from late 1984 until the weekend before he died almost eight years later, Muldoon hosted a weekly talkback radio programme, Lilies and other things, on Radio Pacific. It was very popular, attracting some 75,000 listeners and twice winning an Australasian broadcasting award for the best programme of its type. Muldoon projected on the programme a more tolerant, patient, kindly and humorous personality than he had as prime minister.

The Queen awarded Muldoon the Knight Grand Cross of the Most Distinguished Order of St Michael and St George (GCMG) in the 1984 New Year’s Honours. Thea Muldoon became a Dame of the British Empire in 1992.

After leaving Parliament, Muldoon continued to host his Radio Pacific programme and chair the North Shore Hospice but from Christmas 1991 recurrent stomach pains, diarrhoea and sleeplessness troubled him. Tests suggested cancer but his heart condition made an operation impossible. He entered North Shore Hospital for further tests and died in his sleep on 5 August 1992. He was 70 years old.

Muldoon was buried in a simple grave at Purewa cemetery after a state funeral in the Auckland Town Hall, at which 100 Black Power members performed a ferocious haka, symbolic of the fearsome reputation he had during his lifetime.

Throughout his career Muldoon, like most politicians, was driven by personal ambition, but he also had a genuine concern for the welfare of those he regarded as 'ordinary' New Zealanders. He believed, however, that he could personally (though paternalistically, and in time arrogantly) discern what was required to achieve, or in times of economic difficulty defend, the interests of those people. In the latter years of his prime ministership he became much more cautious and isolated and failed to realise that his policies were becoming increasingly counter-productive.